Sobriety

What happens when we design in a vacuum?

Samarkand Revitalization: Ideas for Ulugh Beg Cultural Center

COMPETITION | SAMARKAND, UZBEKISTAN

INSTRUCTORS: NEZAR ALSAYYAD, MARK MACK

STUDIO ENTRY SELECTION: AYUMI DATE

COMPETITION TEAM: NAOMI MAKI, JOANNA MARTIN, KENDYS NAM, BEN SATO, MIN SOH

真面目

majime

Earnestness, diligent, sober, steady, hardworking

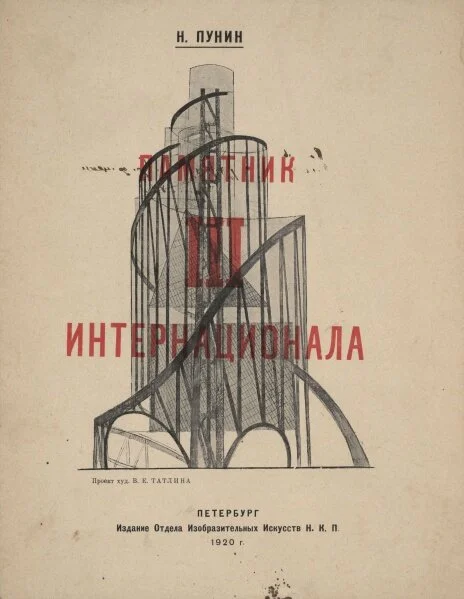

The term 'paper architecture’ was a pejorative reference to architects producing avant-garde work following the Russian clamp down of the mid-1950s, abolishing the Academy of Architecture. Dissenting artists in the Soviet Union were either forced into exile or they chose to leave. Those architects who stayed faced State sanctioned architectural practices consisting of standardized building production. This communist aesthetic deplored any unnecessary ornament or decoration.

Rather than producing such work, the group which dissented, created ‘paper architecture’ as a way of bypassing restrictions and domination, to critique the dehumanizing nature of Russian architecture at the time and the lack of care for traditional building.

Revived in the 1980s, a group of young graduates mainly from the Moscow Architectural Institute took on the title Paper Architects in reference to this period of de-construction, revealing utopian, dystopian or fantasy projects with the specific intention of never being built. As a student of the 80s, the impermanent concept behind paper architecture continues to resonate in my life.

“I am anchored by strong concept-driven design, light, form, movement, color and materials. A wabi-sabi warrior (侘寂侍), my work is guided by the acceptance and appreciation of the transient nature in life.”

Learning when to defend and fight for your design: I recognized this internal struggle to honor yourself and to respect the client’s wishes and prerogatives. There is a sobering reality in the time designers spend to diligently create commissioned work, only for the design to be disregarded. Specifications of resources change–supply chain, scheduling conflicts and value engineering–and play a role in the potential demise of a design.

As a student, my love of competitions came about as an outlet of creating designs completely of my own. They became a celebration and path to my sobriety–acceptance, learning humility and the art of letting go.

read more

Cornell University first introduced me to competitions as a Socratic tool. The Socratic method uses questions to examine the values, principles, and beliefs of students. Through questioning, students strive first to identify and then to defend their work. For me, these competitions represented a non-biased, merit-based evaluation on how effectively one conveys the same set of parameters, bringing forth our own creative assumptions and imagination.

However, my formidable academic achievement came while I was attending University of California at Berkeley. The Department of Architecture sponsored three finalists in hopes of winning one of five spots open to receive $30,000 at a recognition ceremony in Samarkand, in southeastern Uzbekistan, one of the largest and oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. The first was an entry of a Christopher Alexander-led collaborative studio work, the second was Nezar Alsayyad and Mark Mack’s computer-aided submission and the third–mine, the coveted student entry voted on by my instructors and classmates.

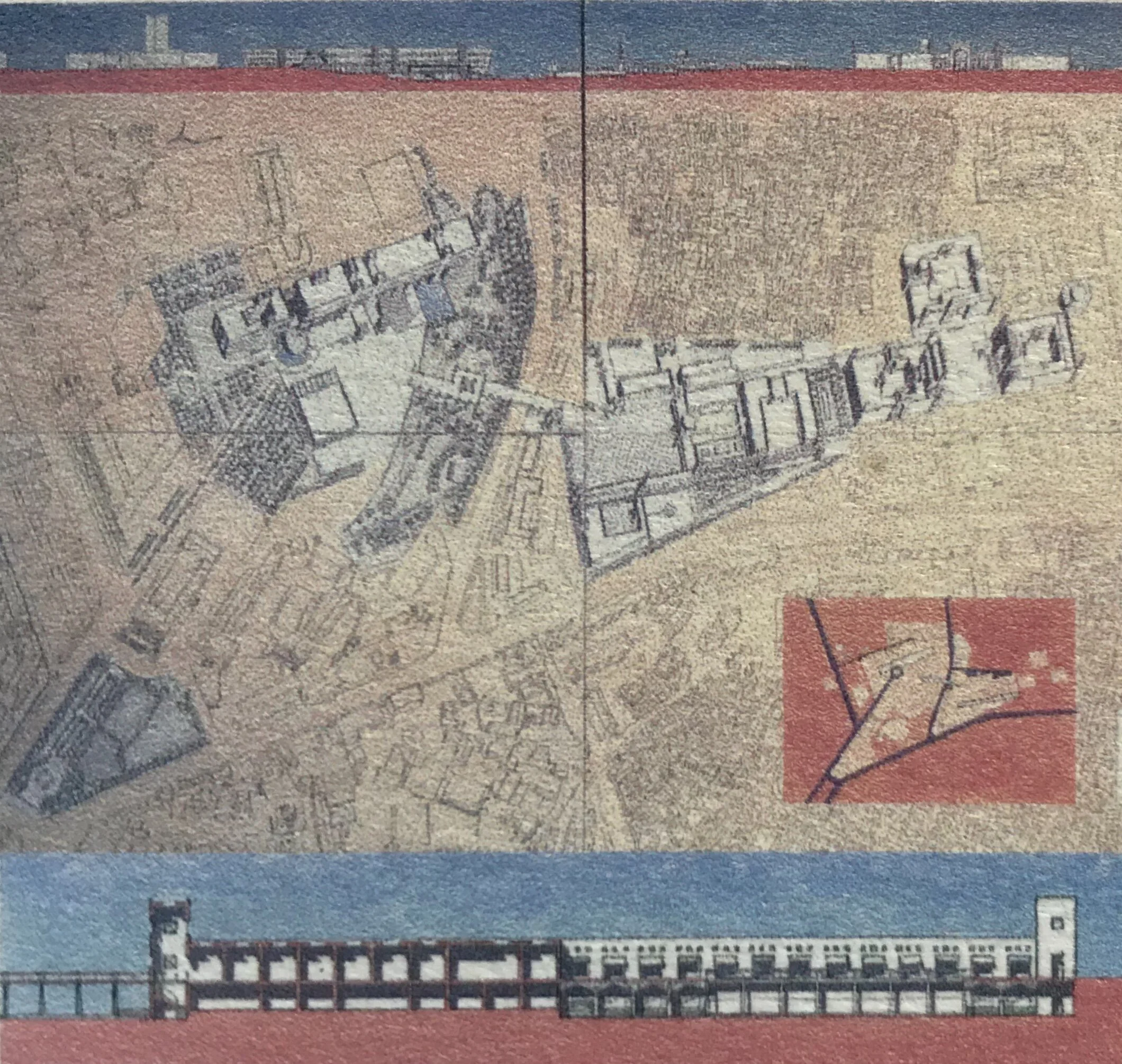

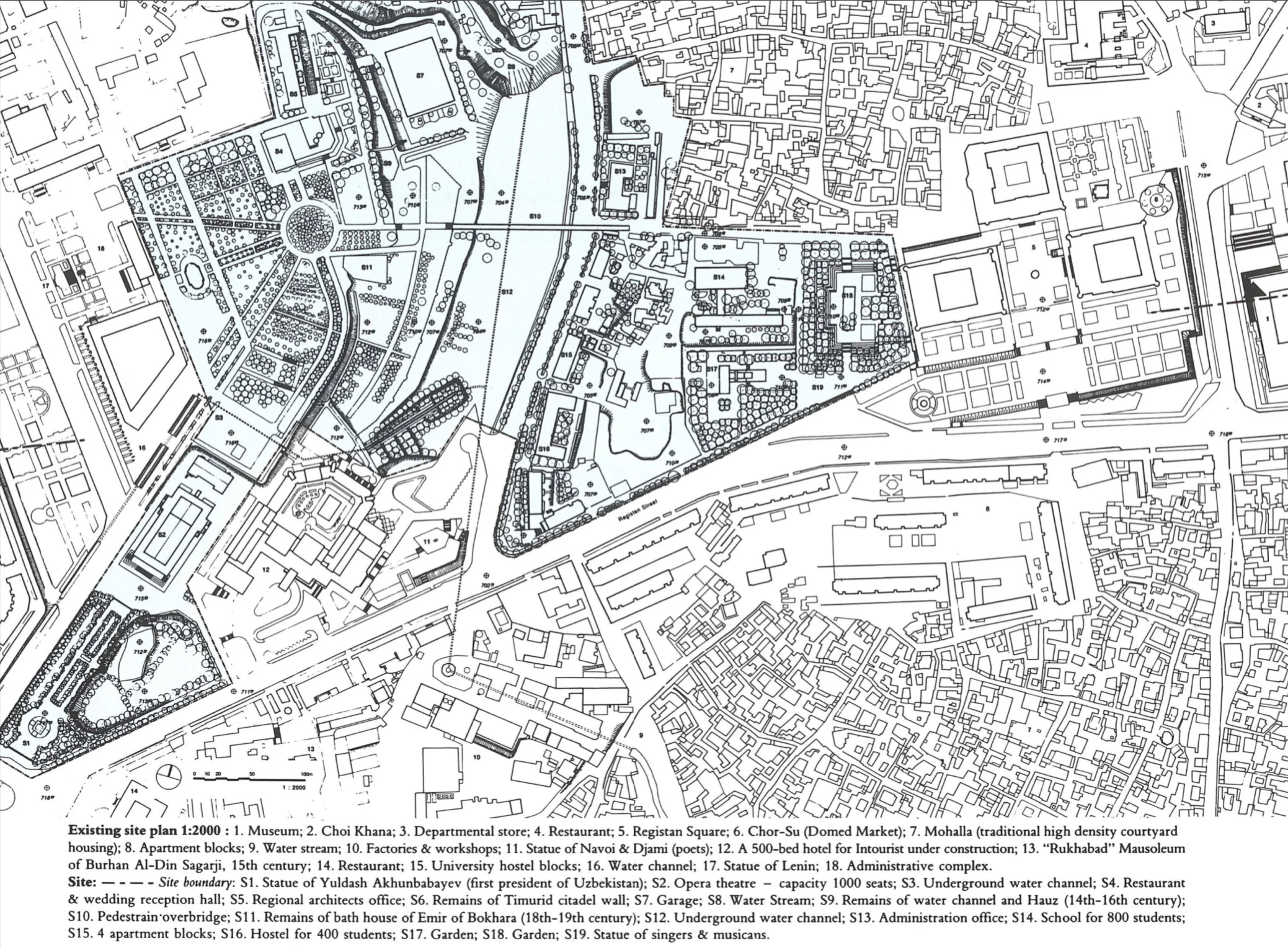

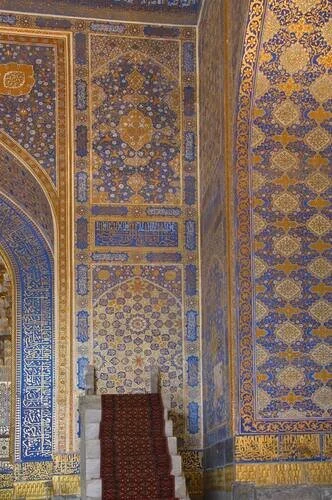

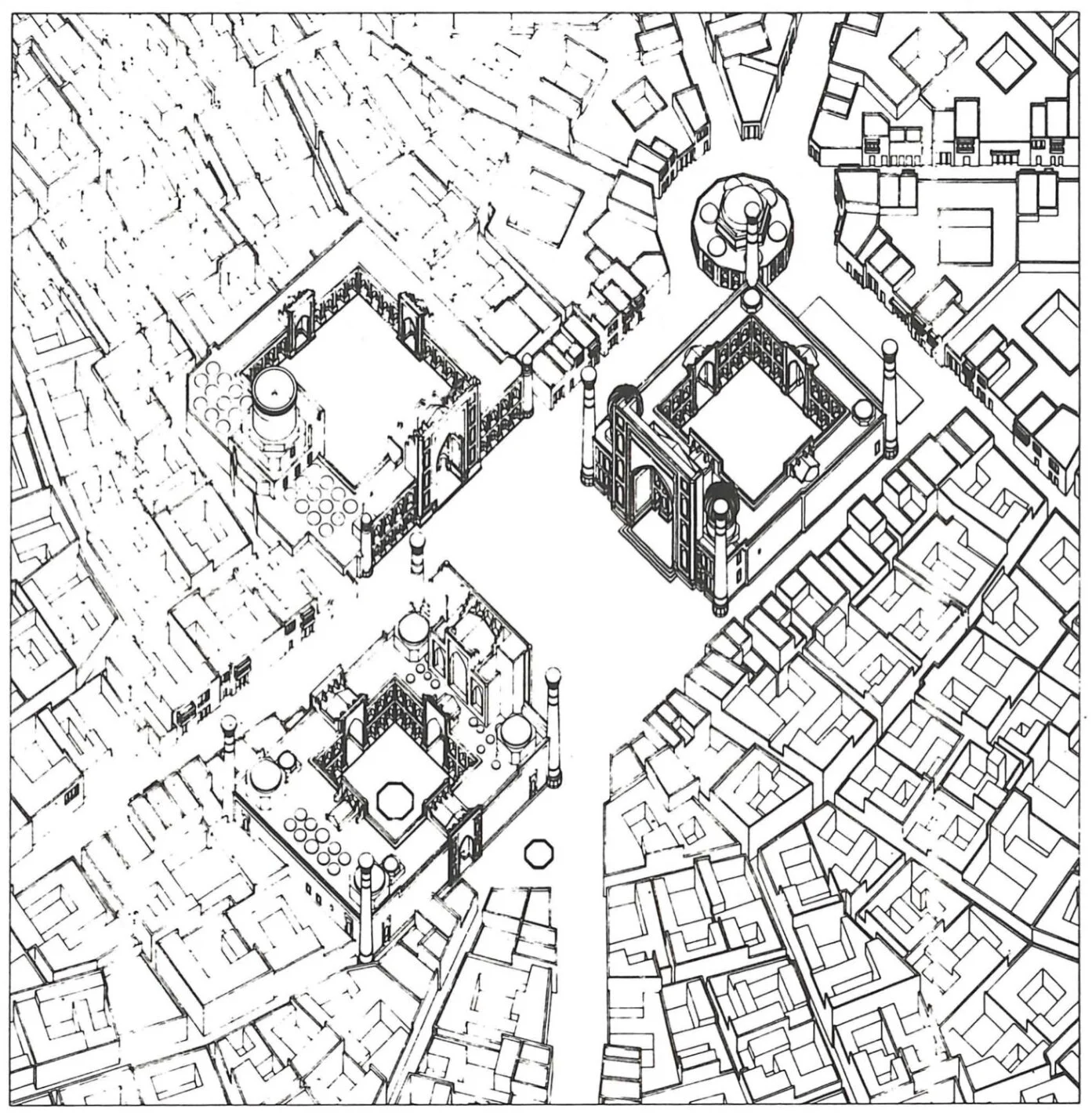

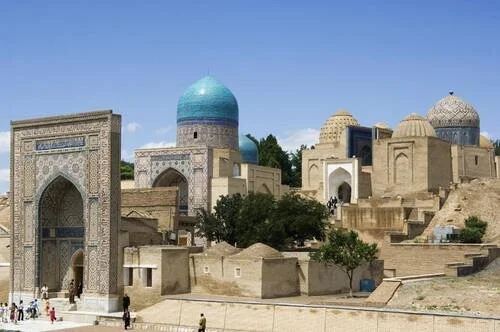

The competition called for proposals to develop a site of 25.5 hectares in the heart of Samarkand, creating a new cultural complex. The site occupied the space between the spectacular Registan Complex and the old city of Samarkand on one side and the modern city with its motorways, boulevards and remnants of 1950’s Soviet office buildings on the other.

The uniqueness of the site also introduced a specificity and a realism not usually encountered in a competition of ideas. My scheme recognized Samarkand's unique heritage, The Registan. The complex, built over two centuries, is one of the masterpieces of world architecture. It cannot be taken lightly in any composition. But it ached for a transition or a recognition with the modern revitalization. My entry focused on dialogue between the past, present and future.

More than 50 Berkeley academics spent the Spring of 1991 exploring an enigmatic country. While our professors were breaking ground in building a computer model of the competition site, the students in our studio manually built a communal chip board topographic model so that we could all share it as a class. Often prickly, harsh, combative and competitive, the academic environment softened as we each explored our ideas. The masterful shepherding by our professor recognized concepts for each student. We were too busy defending and getting our concepts to emerge independently that we were not competitive with each other.

When my entry was initially selected, generous classmates offered to help prepare my submission. My team donated their time and talent, but most of all they championed me to finish with their sheer camaraderie. Most of these colleagues remain close friends. I remember being too exhausted to be thankful, and collapsing into a pool of relief tears upon returning home. And the nothingness experienced after never hearing the result until months later when the winners were announced. My carefully created design boards created by my hands and my colleagues were never to be seen again. It was humbling.

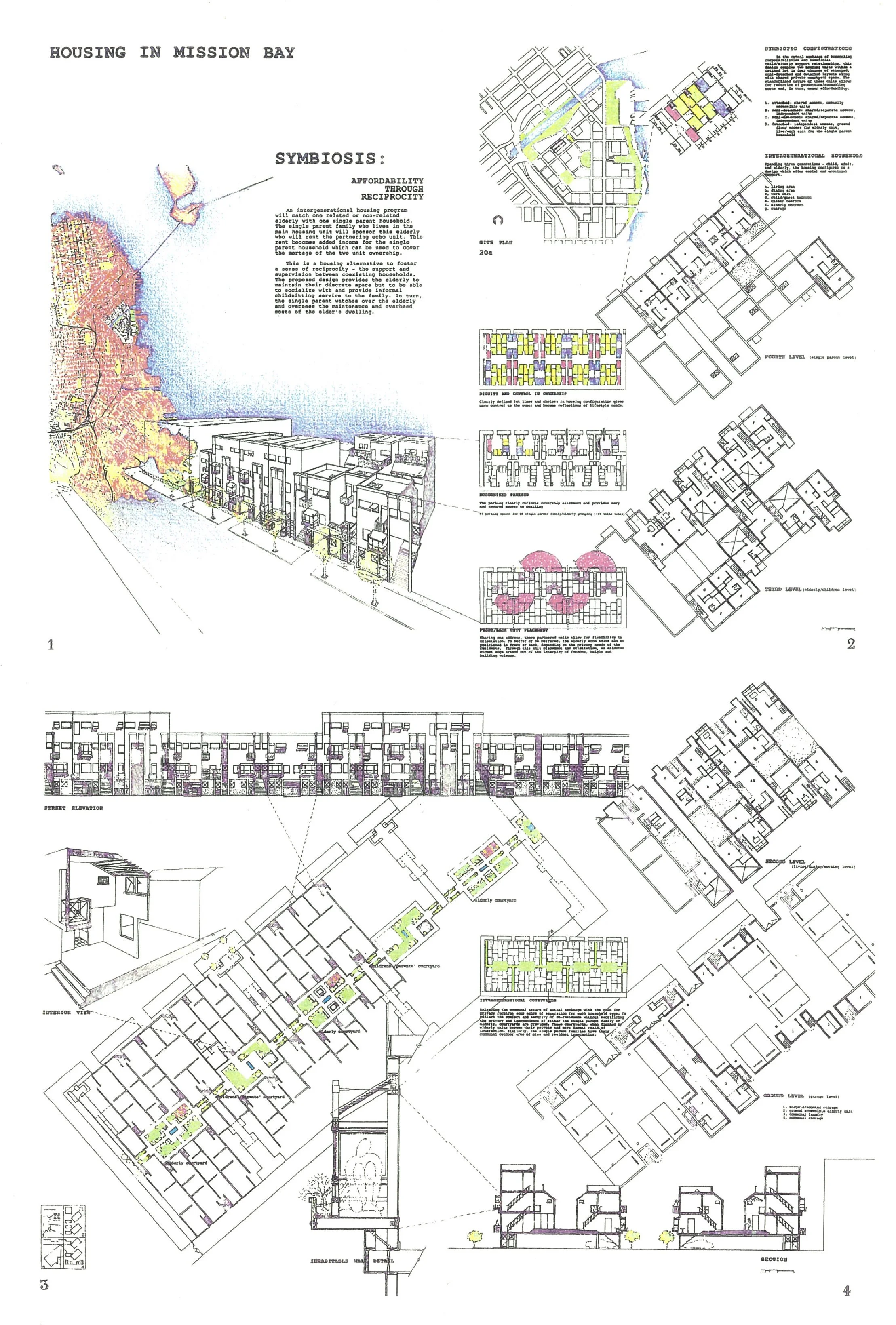

Sobered up and rested, I vowed to try again. So when another competition coincided with my interest in affordable housing, I incorporated it into my thesis in 1992. My submission was recognized, exhibited and published. My determination to try again, my tenacity was rewarded.

The real “win” does not reside in the judgement of others. There is wisdom in a lived experience in which we are able to choose how to remember our experiences; our skills are sharpened no matter what. There is gratitude in recognizing the sobering nature of hard work that may go unrewarded.